It's February and someday when I see my kids in person, I will have no idea who they are. Some student will be like, "I'm so-and-so," and I'll go, "Oh, you're the anime character!" because that's the profile picturing that has taken the place of their face for the past five months.

But here's the thing: I will know probably more about each individual student than I knew about my students when we were face-to-face. Yeah, I may not know what their actual face looks like, and for a lot of them I may not know the sound of their voice, but we've had conversations almost every single day. They just have looked different. They've been private messages in Zoom, email conversations, journaling back and forth, etc.

When we take away our disappointment that cameras aren't on, we can notice that we have built relationships, and we are invested in and informed about the lives of these kids.

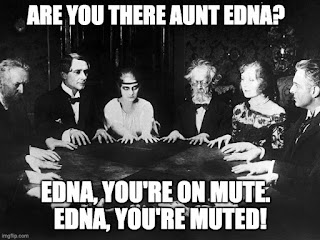

However, this doesn't fix the dreaded awkward silence of a Zoom class after you ask a question to a sea of little black boxes with the mute sign showing for all of them. It seriously feels like some sort of seance.

The most difficult part about teaching a synchronous, online class is that, even though students are willing to interact with the teacher, they are terrified to interact with each other. No one will answer a question out loud, no one will turn their camera on, and breakout groups are more awkward than a middle school dance.

It's hard for me to know that I've built relationships with my students, but they are terrified of each other. That doesn't result in a safe learning environment, and we know that the brain can easily kick into a fight, flight, or freeze mode without a sense of safety.

While this can't be completely fixed, a large portion of it can be addressed and improved with an intentional focus on creating psychological safety for students. The big question is, "How do I do this in an online environment?"

Here are a few of the major ways that you can do it:

1. Routines, routines, routines.

The brain needs patterns. When things are predictable, we aren't on high alert for some unknown threat. Think about this from a purely biological stance. If you are in a haunted maze and don't know what's hiding around the next corner, how well is your brain functioning? How willing are you to engage in risk-taking? How well can you engage in complex thinking? Not well. The same is true with students. If they show up and don't know what to expect, they are going to be on high alert looking for potential threats. Think that prompts a willingness to engage in a group? Try again.

Here are some things that you can do to help establish these routines.

A) Create an opening slide. Every day when students show up to class, what can they expect to see? For my students, it's this slide (taken directly from today):

It creates a sense of routine for my students, and every day when they log in, they know what's going to happen. I'm not saying you have to spoil everything, but help students get past the "What if..." questions that make them feel like there is always a potential threat in the next activity. Put everything out there right away.

B) Share a weekly (or more) schedule.

I know that everything is changing right now, but as much as you can, let students know what's coming. Writer's workshop day requires the most risk-taking from my students, in terms of social interaction, so I let them know at the beginning of the week what they are sharing on Friday, and then I remind them again every single day. This way they can prepare. If they know they only have to share their favorite sentence, they have a week to choose it, practice reading it, etc. This doesn't have to be fancy. In fact, here's mine as an example of a non-fancy schedule:

C) Create a weekly structure and try to stick close to it. My weeks look like this: Monday is independent writing (with some conventions practice), Tuesday is a short mini-lesson and practice, Wednesday is a game-based formative assessment, Thursday is group work, and Friday is writer's workshop. Knowing the basics of what happens every day has helped my students be more able to engage in it. (I feel like I should stop here and say that I still stare at black screen and listen to the echo of my own questions, too. This is just what has made some improvements in how often I have to do that.)

There's no way to keep the routines 100% consistent, but the more we can remove those blind corners that might hold a figurative scary monster that will jump out at students, the better.

2. Welcoming Environment

How the heck do we do this in Zoom? It's a computer screen and kids are in their own houses?! Yes, there is a ton that we can't control, but think about what we do control. How do we help students walk into a space that calms them, makes them feel welcome, makes them smile?

Here are some of the things that are working for me:

A) Play music when kids come in. There are plenty of cognitive reasons to play music in the classroom, but one of them is that music can help bond groups of people together. Plus, it gets the energy up. As a bonus, have students pick songs (obviously within limits).

B) Say students' names as they enter the room. (*Cue Destiny's Child*) Yes, they are just faceless boxes on a screen, but we all pay attention a little more when we hear our names. Plus, it lets the students know that we see them, that we notice them. I even will just randomly use students' names while I'm talking during class. We want to be known. It makes us feel welcomed when we're know. Names are a big part of that. (And as a note: say their name correctly. Have them record a video introducing themselves and saying their name if you need to practice.)

C) Prioritize personal and informal interactions. Along with names and feeling known, help the students feel welcomed by getting to know them. In the traditional classroom, it was easy to pull a student aside to chat with them. It's hard in Zoom because everyone's always listening when you're all together. Some of my favorite ways to have these personal interactions and through individual emails (I try to email five students per class, per week), private chat in Zoom, and my ultimate favorite – individual breakout rooms. With all of this, keep track of who you are talking to. It would be awful to miss a student or not notice a bias in your student interactions. I have also found that the informal space before class starts typically gets more discussion from my students. Use that to build confidence for the more formal interactions.

3. Scaffold Up Competence-Confidence Loops

If you've never heard of them before, the competence-confidence loop is simply the idea that when we feel competent in something, we are more confident to take a risk, and when we feel competent in that new thing...you get the point.

For this, think about how you could allow students to see success regarding the topic of the interaction before the interaction begins. Here are a few ways that I like to do that:

A) Gather responses ahead of time. Often times I'll end my class with a question for students to respond to, and then use that same question again in the next class for collaboration. The key is that after I've gathered the responses, at the beginning of the next class, I will use the private chat to tell specific students what they did well and then encourage them to share out. It doesn't always work, but knowing you have something of value to offer definitely increases our willingness to share our ideas.

B) Collaborative responses. Padlet has been my bread and butter during remote learning, and part of the reason why is because I think it's so crucial early on in a discussion to be able to get a sense of where everyone else is at. Often I will have students write down their response on Padlet, give everyone time to read them, and then ask a few students to highlight important things they saw. That way, even the student who wasn't sure of their response at first can offer something of value in the discussion. Plus, it helps students see learning as a communal process, not an isolated one.

C) Have students identify their strengths. Before you send students into a collaborative activity or begin an interaction, give students this prompt: "Think about all the things you can offer this group. What are you good at? What are you knowledgeable about? What type of role do you fill well in a group?" Remind them that they are not just the sum of their grades, but that each student has a unique skill set that they can offer to the group.

Final Thoughts:

Truly, a lot of the reason that students won't interact during class is that this pandemic, this year in general has causes them to feel surrounded by chaos, scared, unsure of things. We can't fix that, but we can create a space that attempts to minimize it. Do we want students to interact? Absolutely, but that shouldn't be our primary goal. Our primary goal is to create a space where students feel comfortable, safe, known, and valued. If they happen to be more comfortable interacting afterwards, great, but don't make that your primary goal.

This is really hard, friends. It's discouraging. It's demoralizing.

I hope that you can walk away from this post with hope for tomorrow to just make it a little bit better. You can. You will. Hang in there.

Comments

Post a Comment